One Phone Call Led Luis Ribas to a Long and Fruitful Career as a Foreign Correspondent

Luis Costa Ribas is award winning journalist, editor, and television correspondent with over 40 years’ experience in the United States and abroad working on all media platforms. He is currently a U.S. Correspondent for CNN Portugal, where he has reported extensively on domestic politics including, more recently, the legal troubles faced by former President Donald Trump and the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. Previously, Ribas worked as a U.S. Corrrespondent for TVI, one of Portugal’s top television networks. He also enjoyed a long career with SIC, another Portuguese network, serving first as the U.S. Bureau Chief in Washington, D.C.; then as a Senior Corrrespondent, and finally as a U.S. Correspondent. In between, he had a stint at VOA in D.C. and has worked in communications and documentary production.

Luis Costa Ribas

In the following interview, he speaks at length about his career and shares key insights about the journalistic profession.

How did you get started as a journalist?

Happenstance. I always loved reading and writing. My father was a news junkie, bought the newspaper everyday and the evening news on television was required watching. I had started working for the Ministry of Health, when my father showed me a newspaper ad: “Reporters needed, with or without experience” and a phone number. I called in, was told to do a report on May Day celebrations happening in a fews days time, did really well, and was hired on the spot when I brought my copy to the newsroom editor.

Can you share your experience as a CNN Portugal correspondent working in the United States? What are some of the key assignments or stories you’ve covered during your time there?

I have been with CNN Portugal since its creation, less two years ago. They hired me away from another Portuguese network, SIC Television and its cable station SIC Notícias. In the last 39 years, that included a sting at the Voice of America, covering the 9/11 terrorist attacks, interviewing Salman Rushdie, flying with the Hurricane Hunters and speaking with Bill Clinton are what first comes to mind. But many others were important. I visited 35 US states, and Central and South America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East… and did stories in the heartland and in the cities, on guns and the death penalty, on Wall Street and the cowboy culture, elections and civil unrest in Angola, Mozambique and East Timor, war in Lebanon and natural disasters in Central America. Every story is an opportunity to improve our reporting skills and to learn something new.

How did your experience in the United States as a correspondent shape your understanding of American culture, politics, and society? Were there any specific moments or events that had a significant impact on your perspective?

One of the first things I did, after arriving in Washington, D.C., in 1984, was to go back to university. I graduated in Government and Politics and International Relations at the University of Maryland, and that was critical to advance my knowledge of American history, politics, foreign policy, military, culture, and society. Traveling through the country and being open to what people were saying was just as critical. It’s not so much a specific story or event, but the accumulated experiences from many of those. I see some foreign journalists that, due to sheer differences between their culture and America’s, adopt a hostile or standoffish attitude, prejudicing their coverage, and preventing them from better understanding the country they must cover so they can better explain it to their public.

One does not have to like the U.S. but would be advised to respect the host culture and make an effort to understand it. I did not like George W Bush, but reported with an open mind on the West Texas culture that created him and which is based on religion, cowboys, and oil. I still don’t agree with Bush, but I get why many people do.

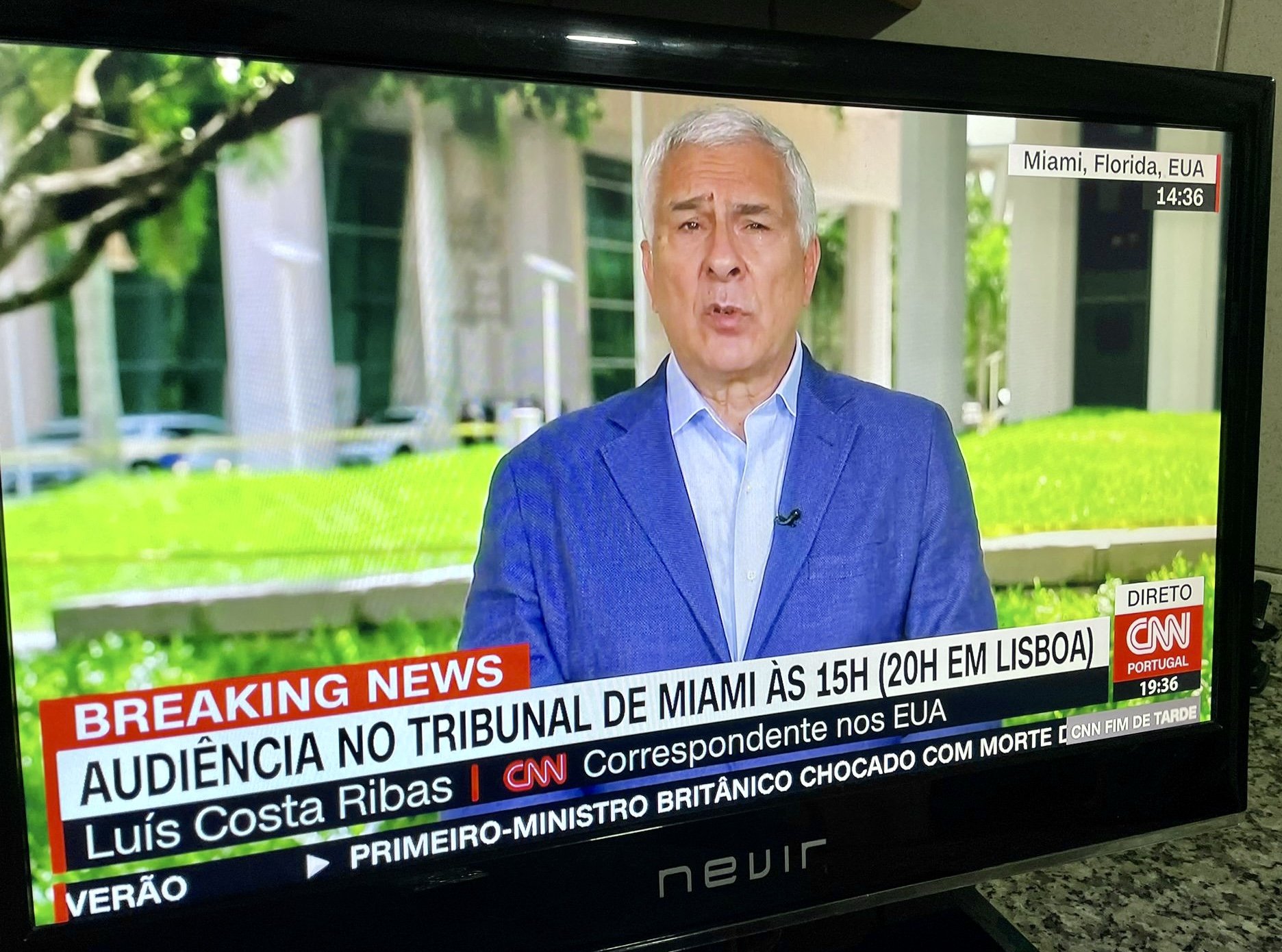

Ribas reporting on Donald Trump’s arrest and indictment in Miami, Florida (2023)

Our role has changed since I first arrived 39 years ago. Back then we reported the news - CNN was just getting started and it did not broadcast overseas, the internet did not take American papers all over the world, and social media was non existent. Now our newsrooms have all those resources, and many people there think they know as much as, if not more than, we do. They don’t and we must disabuse them of the notion that they know America as well as we do. But without a honest effort to understand, and embed with, the American society, that will not happen.

As a foreign correspondent, what were some of the challenges you faced while reporting in the United States? How did you navigate cultural differences and potential language barriers to effectively communicate news stories to your audience in Portugal?

The most critical challenge is access. Unless you work for the BBC or another major international media, few people are interested in talking with you. So, I always looked to people with an interest in Portugal or Portuguese immigrants such as the Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New Jersey congressional delegations, and developed important relationships with them. My reports for SIC Television were seen on U.S. cable systems by the Portuguese immigrants who were their constituents. Barney Frank (D-MA) was exemplary, John Kerry (D-MA) was good as when he was up for reelection, then Rep. Bob Menendez (D-NJ) was good, Patrick Kennedy (D-RI) was a waste of time. But it worked.

Now, as a correspondent for a CNN affiliate I have access to some CNN resources in the United States, and operationally that has made my life easier. On the other hand, some interview requests are denied because they already spoke with CNN America, and it’s harder to get content when your sources think you came use CNN’s materials. Before that, I worked with agencies such as APTN, Reuters Television, and CBS Newspath. Don’t be a small fish in a big pond; working with a larger organization helps you gain access to big events such as Republicana and Democratic conventions, election night campaign headquarters, presidential inaugurations, etc. The Foreign Press Centers are also useful.

They used to have a manual for newcomers with rules for everything, from obtaining a drivers license to credentialing and public transportation. Check them out. As for the language barriers, if your English is not up to par, please don’t be a correspondent in America. On credentialing: everyone should get Congressional accreditation, as that opens up doors to accreditation at State, the Pentagon etc. Besides, if you have a “Press” card from your country it’s pretty useless here: the official looking Congressional press pass will be more helpful in identifying you as a legitimate member of the media.

Ribas reporting on Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans (2005)

Can you discuss any notable differences or similarities you observed between the media landscape in the United States and Portugal? How did you adapt your reporting style or approach to cater to the expectations and interests of your audience in Portugal?

There’s no comparison between a small county of 10 million people and a country of 330 million that straddles a continent. So I won’t even go there. As for the second part of your question, I don’t think I can share anything much too meaningful, as styles are personal and so any adjustment is personal too. I would keep in mind how our work changed. Many media companies think that sending a young kid with a smartphone set up on the street will suffice but they get thin and insufficient results. In addition, social media can make a correspondent’s job harder for two main reasons: 1) because many newsmakers use it to circulate materials and everybody has immediate access to it, so reporting on it will not be of any use to the correspondent; and 2) some journalists tend to be obsessed with going viral on their feeds and forget to keep their work serious, relevant and deep. Going viral does not equal good reporting.

Were there any particularly memorable interviews or interactions with individuals or groups in the United States that left a lasting impression on you? How did those experiences contribute to your overall understanding of the country and its people?

Former President Bill Clinton, novelist Salman Rushdie, singer and maestro Plácido Domingo, astronaut turned senator John Glenn, UN Secretaries-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali and Kofi Annan, Nobel laureate José Ramos-Horta, guerrilla leader Jonas Savimbi, and so many others. Their perspective educated my understanding of the bubble and world they lived in, their actions and decisions. In addition, they bring world perspective: a U.S. based correspondent needs to have a pretty good understanding of the several regions of the world where the U.S. has an interest, in order to be able to cover American foreign and military policy.

Ribas interviewing a rebel leader in East Timor who later died trying to assassinate the President (2006)

What insights or lessons did you gain from your time as a CNN Portugal correspondent in the United States that you believe have enhanced your journalism career? How do you apply those insights in your current role or future assignments?

The priority is to assure you are useful to your company, you know things about America that they don’t, you can offer deeper and more insightful perspective on current events. Read good books (such as Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Leadership in Turbulent Times, and many others), subscribe to publications such as Foreign Affairs and The Atlantic so you can follow the many debates in America, beyond the superficiality of cable and social media. Educate yourself on the Constitution: most of America’s problems are rooted in it and in the difficulty of running a XXI century democracy with a XVIII century Constitution, as interpreted by an out-of-touch “originalist” majority in the Supreme Court (read Laurence Tribe’s On Reading the Constitution and Uncertain Justice: The Roberts Court and the Constitution). Look for experts at major universities’ web sites (they have catalogs of specialists), as well as CSIS, CATO, American Enterprise Institute, The Arms Control Association, etc. Be well informed so you can inform better, contextualize better, explain America better.

Alan Herrera is the Editorial Supervisor for the Association of Foreign Press Correspondents (AFPC-USA), where he oversees the organization’s media platform, foreignpress.org. He previously served as AFPC-USA’s General Secretary from 2019 to 2021 and as its Treasurer until early 2022.

Alan is an editor and reporter who has worked on interviews with such individuals as former White House Communications Director Anthony Scaramucci; Maria Fernanda Espinosa, the former President of the United Nations General Assembly; and Mariangela Zappia, the former Permanent Representative to Italy for the U.N. and current Italian Ambassador to the United States.

Alan has spent his career managing teams as well as commissioning, writing, and editing pieces on subjects like sustainable trade, financial markets, climate change, artificial intelligence, threats to the global information environment, and domestic and international politics. Alan began his career writing film criticism for fun and later worked as the Editor on the content team for Star Trek actor and activist George Takei, where he oversaw the writing team and championed progressive policy initatives, with a particular focus on LGBTQ+ rights advocacy.